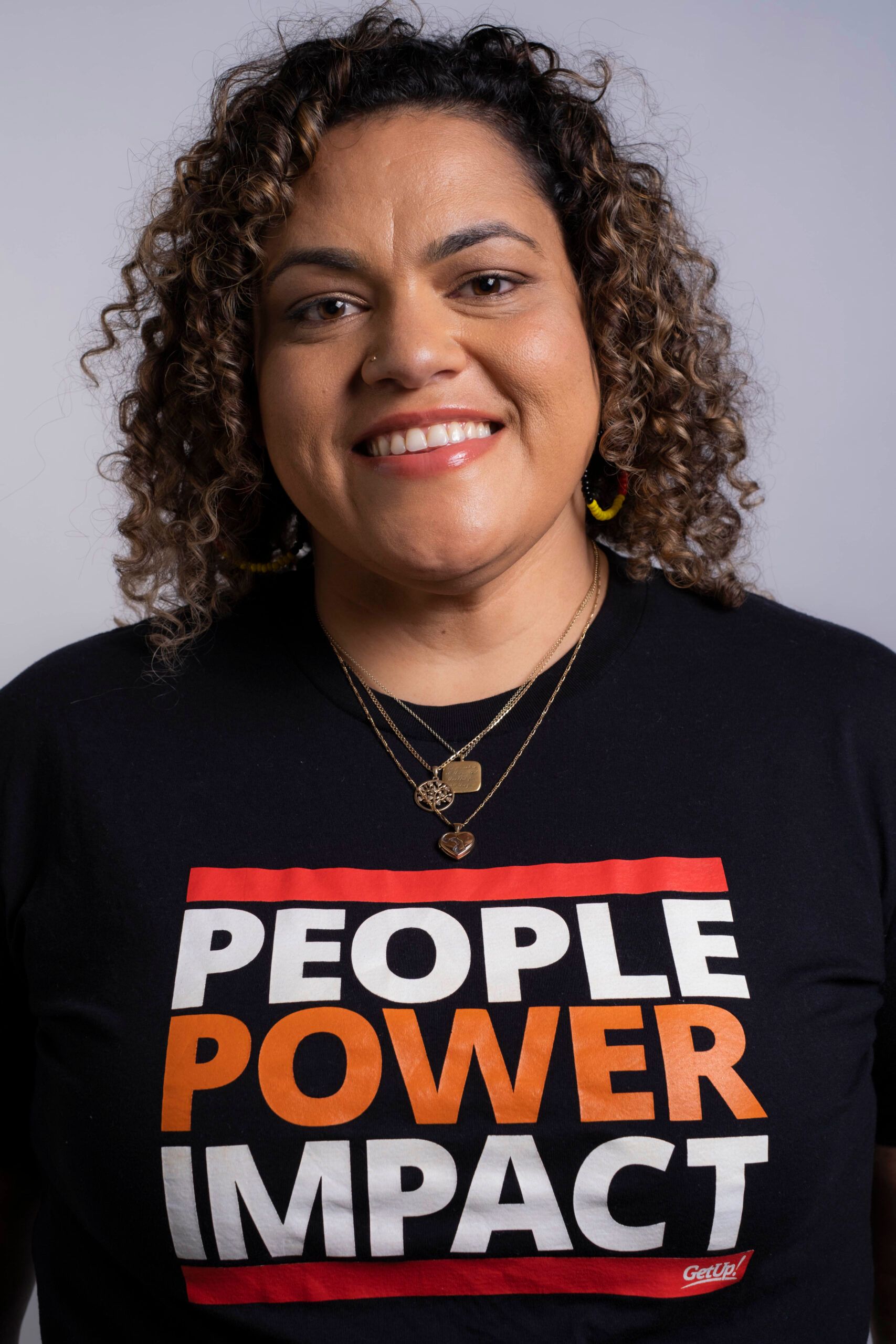

The Queensland Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) highlights the significance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights, in particular their right to self-determination. This month, I caught up with proud Widjabul Wia-bul woman, Larissa Baldwin-Roberts, who among many other community commitments is the CEO of GetUp! and Director of Research for Passing the Message Stick—a First Nations-led research project designed to shift public narrative in support of First Nations justice and self-determination.

A strong advocate for First Nations people’s rights and justice, Larissa is currently campaigning for a Voice to Parliament to be constitutionally enshrined. We talked about what it means to be represented, the role of self-determination in the Voice to Parliament campaign and the importance of Blak Advocacy to implement change.

Busy connecting with First Nations communities across Australia, Larissa spoke to me from her car on Wurundjeri country before heading off to her next destination. She reminded me that self-determination is a right for everyone to enjoy, yet it is seen as a “special right” when applied to First Nations people.

“First Nations people do have inherent and different rights in this country,” she said. “As First Nations people we never ceded our sovereignty, and that is just a fact. We do have rights to land. But those rights have never taken away anything from non-Indigenous people… The opposite has happened for us… we need laws to enshrine self-determination for First Nations people.

“Not because it’s a special right, but because on balance we make up such a small percentage of the population that there is no way for us, in a popular vote, in a democracy, to express our view.

“It’s really important that we have democratic institutions in this country for First Nations people. How are we represented otherwise?”

The stigmatisation of First Nations peoples gaining ‘special rights’ comes from a deficit narrative that Larissa says belongs to the opposition: “The idea of a Black armband view of history, special rights and scare tactics against native title, these things are very persuasive for most of the population who haven’t met First Nations people, or really know anything about us. They really rely on these ingrained stigmatisations about us.”

Larissa Baldwin-Roberts

GetUp! CEO

Larissa says you can only defy this narrative with a logical argument. “If [First Nations people] were saying, ‘hey, we need more power in order to determine our own future’, [then] I believe we will be able to create systemic change in this country.”

The referendum has sparked a noticeable shift in the way Australians are thinking and talking about what it means for First Nations voices to be represented in determining their rights and addressing issues impacting their communities.

Through the Passing the Message stick research Larissa has learned: “Non-Indigenous people often want to hear the views of First Nations people… one of the things you hear often is: ‘We didn’t learn that in school’. There’s a very limited resource where non-Indigenous people have proximity to what is actually our shared history, and that’s really important, because if you can’t explain the predicament that our communities are in, then what people do is they kind of fill in their gaps themselves,” she said.

“These gaps are unfortunately filled by the deficit narrative and stigmatisation that governments and media use to drive a political agenda.”

Larissa offers an example of how the knowledge gaps around the delivery of healthcare and education in Australia fuel prejudice: “Australia, as a broader nation, believes in the idea of universal healthcare and education. If you don’t explain the disparity in how healthcare services are delivered [to First Nations people] across remote and regional areas, then people think that there is something inherently wrong with us as people, not that our communities don’t have the same equal access to healthcare providers. We don’t have the same access to education and a lot of people don’t expect this.”

Larissa explains that the narrative needs to move “out of the frame of blame and into a frame of what action do we need to take?”. Solutions need to be driven by First Nations voices that have always been present through Blak advocates, but not always heard.

“Blak advocacy has power. It’s one of the most important and powerful things that we’ve ever had in this country.”

“Regardless of what the law of the day or the law of land during that time said, or the policies around segregation and assimilation, there’s been huge challenges that our communities have had to overcome.”

In Australia, First Nations people are disadvantaged across all life indicators, failed by governments and political systems, but First Nations communities have the solutions.

“We want to see change. We need to see change for our community. We need tools for First Nations people to be able to implement their ideas, their solutions.”

A Voice to Parliament brings possibility: “Other nations where you have First Nations people, they have representative bodies. They’re not something to be scared of… It’s really about, if we take this step, what becomes possible politically in this country?… What does this mean to the political psyche in this country and where can we go?”

Larissa spoke to Gimuy Wulubara Yidinji leader and advocate Uncle Gudju Gudju from Cairns who said a no vote would return us to status quo for First Nations people. “The status quo is not good right now. And you can’t say to people that’s all you’re going to get. He’s says that’s cruel. And I agree with that,” she said.

Larissa reflects on the damage caused when First Nations people had their voice taken away during the Northern Territory Emergency Response, widely known as the NT Intervention: “Our communities were shamed into silence and [we] couldn’t talk about how government policy wasn’t working, because all of a sudden, we were accused of awful things that weren’t true. And it was right across the media, and people believe these things.”

Larissa sees the Voice to Parliament as an opportunity for First Nations communities to determine who should represent their voice at a national level: “At a very pragmatic level, I look at the Voice to Parliament as just a representative body, and I think representation matters so much and I do believe that we do need to settle the conversation of who speaks for us.”

“There is no one silver bullet and no First Nations person is approaching this like it is a silver bullet.”

Larissa reminds me that the Indigenous worldview is that of a collective not an individualist one. Decisions are made by way of consensus: “We’re having a discussion. This is our politics playing out right now. It is possible for us to make a decision on this. It’s not going to be ready and shiny for everybody else. We’re working it out ourselves.”

A shared and equal enjoyment of our rights as a nation cannot happen if we continue to return to a political silencing of First Nations people in this country. Larissa has shown me that a Voice to Parliament is not the magic solution to all our problems but rather a platform for First Nations voices to be heard and possibilities to be discovered. The referendum is an opportunity for us all to take action on saying yes to a future where First Nations Australians have equal access to human rights.

“[First Nations people] don’t have the power to vote by ourselves to create the kind of political change that we need.”